Here’s Why You Should “Punish Test” Your Surveys

Testing a survey before it launches takes about 4 to 6 hours of an experienced professional’s time, for a standard ten- to fifteen-minute survey. If you don’t invest that time up front, you are almost certain to discover mistakes while in the field (or worse: after), which can make for a nightmare of programming corrections and redoing data collection.

I sometimes wonder: Do we REALLY need to test so thoroughly? Can we do it more efficiently, maybe in half that time? Then, as a respondent, I suddenly get a mess of a survey (and a good reminder), like this survey that was sent to me:

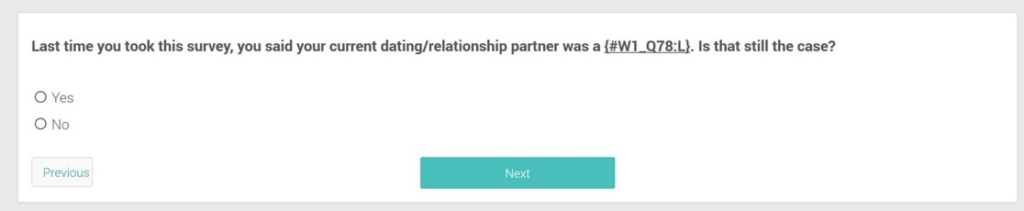

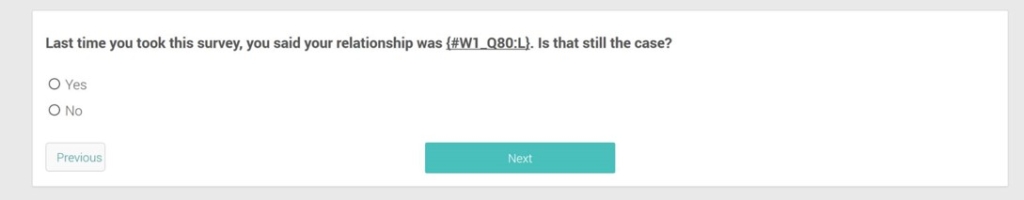

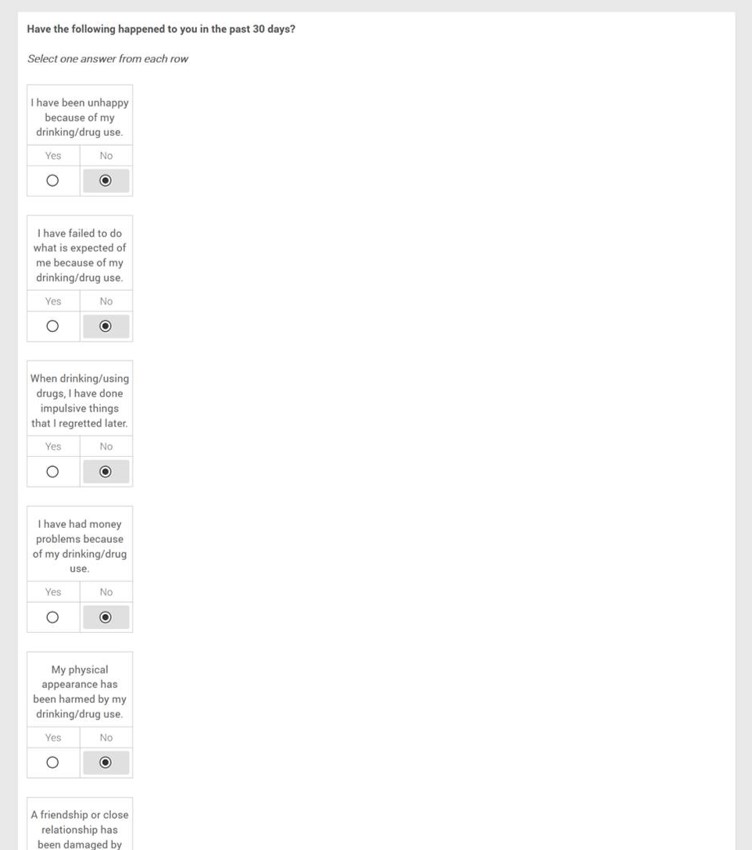

In two of these questions, the text piping does not work. And then one question renders incorrectly on a desktop, displaying in a narrow vertical format, which is appropriate for a mobile device, but not for a desktop.

These mistakes were not made by amateurs. The survey was sent to me by one of the top-3 market research firms in our industry (because I participate in their ongoing probability-based research panel of U.S. adults). Plus, the survey was sent on behalf of a research group at an academic institution collecting data for a longitudinal study on health and social behavior.

It just goes to show: YOU (and we) can do better than the most prestigious firms working on behalf of the most prestigious clients … with simple best practices like rigorously testing surveys. It takes more than “running through” the survey once or twice to make sure it looks good and functions okay. Check everything: the skips, the logic, the words, the text piping, the item randomization, the instructions, the choice sets, the text boxes … the list goes on.

If you don’t have the time or patience for devoting at least a half day to testing your questionnaire (or if you don’t have the tools, checklists, random data generators, and so on) then hire a firm like Versta Research or another expert firm to do it for you. Trust me when I say it is worth the small investment up front to avoid the punishment of junk data at the end.

—Joe Hopper, Ph.D.