This Is What “Sugging” Looks Like: A Fake Survey that Is Unethical and Hurts Real Research

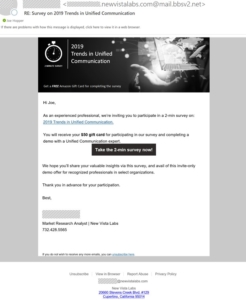

It really bugged me that I got this “survey” invitation last week, in part because it conforms so well to many of the best practices we advise for designing effective survey invitations. Take a look:

It offers a generous incentive. It has a nice graphic saying how long the survey takes. It has a prominent call to action with a big button (Take the 2-min survey now!) It has a signatory that looks like a real person with a job title, company, and telephone number. It (partially) complies with spam laws with the opt-out, address, and other information provided at the bottom. It looks a lot like the survey invitations we send out, and we get excellent response rates.

It offers a generous incentive. It has a nice graphic saying how long the survey takes. It has a prominent call to action with a big button (Take the 2-min survey now!) It has a signatory that looks like a real person with a job title, company, and telephone number. It (partially) complies with spam laws with the opt-out, address, and other information provided at the bottom. It looks a lot like the survey invitations we send out, and we get excellent response rates.

But this is a sales pitch, not a research survey, which is maddening. Real research would never provide a $50 incentive for completing a demo with an “expert.” The company name “New Vista Labs” is fake, as far as I can tell. The phone number and address belong to a B2B sales lead generation company. The signatory is probably not a real person, and if he is real, he is a sales guy, not a market research analyst.

This is a perfect example of “sugging,” which stands for Selling Under the Guise of Research. The American Association of Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) describes sugging as:

… gain[ing] entry or acceptance in order to make a sales pitch by initially defining the contact as being made for “research” purposes. This trades on the prestige of science, and it exploits the willingness of the public to reveal information about themselves in the public interest. In some cases, questions establish respondents’ susceptibility to sales pressure or their interest in some product or service. Follow-up contacts are then made to those so identified, all under the guise of “research” (sugging).

It is not just deceptive; it is sometimes illegal. Four years ago, Carribean Cruises and several call centers it hired were fined millions of dollars by the FTC for sugging.

Sugging diminishes the efforts of genuine research, preying upon the goodwill of people who want to participate in legitimate research. Thankfully, AAPOR identifies it as a practice that they (and we, as members of AAPOR) condemn in the strongest terms (see AAPOR’s Condemned Survey Practices).

Reputable companies and reputable researchers never, ever do this kind of “research.”

—Joe Hopper, Ph.D.